Newer Discipline Practices and School Safety in Wake County

In September 2017, two students were stabbed, and one was murdered at a public school in New York City. Some have blamed the school’s ineffective alternative discipline practices—practices that were adopted in response to guidance from the Mayor’s office to avoid major discipline referrals and suspensions. NC public schools are also developing and implementing alternatives to suspensions and expulsions.

Could it happen here in Wake County?

Over the past decade, public schools in the state of North Carolina have been actively encouraged to replace more traditional methods of applying discipline—typically, punishments for misbehavior—with Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports (PBIS), which is often referred to as “School-Wide Positive Behavior Supports,” or SWPBS. We discussed PBIS in our previous piece on this topic. The NC Dept. of Public Instruction (DPI) started to study PBIS and to create pilot programs from 2000 to 2003. A PBIS State Coordinator position was created by the General Assembly in 2007, and the first Coordinator started on the job in 2008. Multiple behavior consultants are now on staff to support NC public schools by region.

The school district here in Wake County has implemented a version of the state-supported PBIS infrastructure. As just one example, the principal of Forest Pines ES in Raleigh, Dr. Patrick Grant, described that school’s PBIS program in a letter to parents as “a proactive systems approach for creating and maintaining safe and effective learning environments in schools, and ensuring that all students have the social/emotional skills needed to ensure their success in school and beyond.” Like multiple schools in the district, Forest Pines first implemented PBIS in during the 2006-7 school year. Grant writes that “The foundation of the approach emphasizes teaching students the behaviors we expect to see, reminding them to use those behaviors, acknowledging them when they do, and correcting them when they do not.”

In June 2017, the Wake Board of Education amended its Code of Student Conduct to alter the guidance on suspensions. It now reads, in part,

Recognizing that removal of students from school can exacerbate behavioral problems, diminish academic achievement, and hasten school drop outs, the Board encourages teachers and school administrators to use in-school disciplinary measures when possible and to reserve out-of-school suspensions for more serious misconduct, such as behavior that threatens the safety of students, staff, or visitors or threatens to substantially disrupt the educational environment. Except to the extent that North Carolina law requires school administrators to recommend a 365-day suspension for any student who violates Rule IV-1 Firearm/ Destructive Device K-12, this Code authorizes, but does not require, the use of out-of-school suspensions.

The policy also includes a statement that one of its aims is to “encourage the use of behavioral supports and non-disciplinary interventions as alternatives to exclusionary discipline.” At the time when the new policy was adopted, committee chair Jim Martin was quoted in the Raleigh News & Observer as saying, “The goal is to try to shift our approach from punishment-based discipline to discipline by engagement.”

Both by policy and in the media, the Wake school board is definitely putting pressure on school leaders to reduce suspensions, especially of minority students, and especially in the lower grades. They’re responding both to new statutory guidelines from the NC General Assembly and from the federal government. A federal investigation of WCPSS discipline policies was launched in 2010, and—apparently in response—the district reduced the total number of suspensions by 19% between 2011 and the 2015-16 school year.

But are Wake County’s schools less safe now that suspension rates are in the crosshairs? As we discussed in our previous post, some education experts are concerned about safety issues at US schools in response to pressure from the Obama Administration to reduce suspension rates. We can assume that individual teachers are feeling pressure to underreport issues in their classrooms, as happened at the school in NY where the tragic death occurred.

Underreporting issues is obviously less of a safety concern if the term refers to a practice of concealing suspensions by excluding students who misbehave from class, but not logging the incidents as suspensions. (We previously described a Washington Post analysis of DC public high schools that indicated such a practice was very common in the DCPS district.) Another type of underreporting issues with student behavior would be, for example, never escalating from a “minor incident” to an office discipline referral (ODR), even when an ODR is warranted. That type of underreporting obviously presents a greater safety risk.

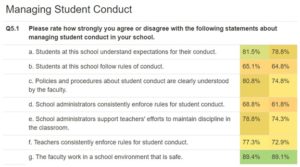

Data from the state’s 2017-18 Teacher Working Conditions Survey indicate that Wake’s teachers are slightly less satisfied with the disciplinary systems and climate at their schools than the average for all North Carolina teachers. The survey, administered in March 2018, received a slightly higher response rate from Wake County’s teachers (92.29%) than the statewide average, which was still quite high at 90.55%. Community support, facilities and resources, and school leadership received the highest satisfaction ratings from Wake’s teachers. Class sizes, discipline policies, rules, and the way rules are communicated to students were among the lowest-rated areas of Wake educators’ job satisfaction. The right column provides data from Wake County teachers’ survey responses; the left column shows statewide averages:

While these ratings are not devastatingly low, they are all lower than the state’s averages in this category. Interestingly, the results from Charlotte-Mecklenburg teachers were very similar, but slightly lower in the “Managing Student Conduct” category. When you consider the 61.8% satisfaction rating that Wake’s teachers assigned to the statement “School administrators consistently enforce rules for student conduct,” it’s worth recalling that multiple teachers and students at the New York school where the student was stabbed to death told a reporter that the administration did not support their efforts to maintain discipline.

NC DPI insists on scrupulous record keeping about disciplinary actions and annual reporting of suspension and crime data. NC statutes require reporting of data on crimes, violent incidents, suspensions, expulsions, and placements of students in alternative learning programs. NC DPI data show that in 2018, WCPSS district schools are still suspending students at much the same rate as the previous three years. A preliminary report from NC DPI listed Wake’s high-school suspension rate for the 2016-17 school year as slightly more than 10%. In all, 11,883 suspensions were issued at Wake County’s schools during the 2015-16 school year, and 11,863 the following year. (Almost all suspensions that are reported statewide are considered “short-term” suspensions; long-term suspensions and expulsions are nearly non-existent in Wake. In 2016-17, for example, Wake high schools reported only two expulsions.)

WCPSS elementary schools issued 2,395 suspensions in 2016-17, mainly for fighting. The rate of suspensions at Wake elementary schools rose every year from 2014-15 to 2016-17.

Similarly, reported crimes that took place at Wake County’s high schools have also increased over the past three years, but not at a shockingly high rate:

| Year | District Name | Reportable Crimes (Total) | Avg Daily Membership, grades 9-13 | Reportable Crime Rate (per 1000 students) |

| 2016-17 | Wake County | 628 | 47,641 | 13.18 |

| 2015-16 | Wake County | 530 | 46,894 | 11.30 |

| 2014-15 | Wake County | 562 | 45134 | 12.45 |

When data from all Wake’s schools is considered, the number of reportable crimes rose by 16.6% between 2015-16 (829 incidents) and 2016-17 (967 incidents). The Reportable Crime Rate for WCPSS as a whole rose from 5.293 per 1000 students in 2015-16 to 6.015 per 1000 students in 2016-17. However, of the 967 incidents reported in 2016-17, 499 were for drug possession. The substantial 25.6% increase in this type of nonviolent crime surely drove a lot of the increase in reported crimes overall. Another large percentage jump occurred when gun seizures were reported. While only one firearm was seized and reported at a public school in Wake in 2015-16, nine firearms were seized in 2016-17.

Analyzing the WCPSS crime data for the News & Observer, Scott Bolejack points out that although the incident rate for Wake rose in 2016-17, it’s still lower than the average rate for the state (6.015 incidents per 1000 students in Wake versus 6.48 for the state). He also notes that of the 55 assaults reported in Wake, five of them occurred at an alternative school that focuses on dropout prevention.

Considering that suspension rates are holding steady and have even increased since the WCPSS discipline policy change in 2017, and considering that most WCPSS teachers who responded to the Working Conditions Survey rated the general safety of their schools highly (89.1% agreement that their school’s environment is safe), the adoption of PBIS and other alternative discipline practices does not seem to have affected the climate and safety of Wake County’s schools. But the crime and suspension numbers are certainly troubling. Wake parents have plenty to worry about from a 25.6% increase in drug-possession crimes and a huge jump in firearms seizures at district schools.

Concerns about the ready availability of firearms and of cheap, powerful illegal drugs, concerns about racial bias in suspension rates, and concerns about suspensions of very young students are perhaps more valid than fears that PBIS/SWPBS and restorative justice practices will soon lead to anarchy or erode safety at Wake County schools.

The more interesting questions to consider here might be:

- Whether the adoption of SWPBS and restorative practices has been effective in

improving either safety or student outcomes. - Whether increases in suspensions and crime rates are in any way related to the

increase in the district’s graduation rate (or more properly, the reduction in the

dropout rate). - Drivers behind the increases in certain types of reportable crimes, such as

larger, societal trends, the county’s poverty rate, the incidences of violence in

our county’s neighborhoods, various pressures on families, and other factors.