The False Promise of School Choice

“School choice” is both a politically charged concept and an ill-defined goal. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos has been a strong advocate for increased parental choice for close to 30 years. She described her 2017 tour of “innovative” schools and school districts as an opportunity to “really highlight and expose to more people the beauty of options and choices and to continue to make the case that all parents, not only ones that have the economic means, should be able to have a decision-making power to make some of those choices” in an October edition of EducationWeek.

But there’s abundant evidence out there that parents are pretty bad at selecting their child’s school. Much hand-wringing accompanied the findings, in multiple research studies, that only 1-2% of students who were eligible to change schools under the school-choice rules of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) act actually did transfer during the policy’s life span. The whole point of those regulations was to read the riot act to schools that were classified as “failing”–to force those schools to make major changes to improve test scores, or else shut down. And parents were supposed to vote with their feet, removing their children from those schools long before they were shuttered.

However, many parents seem to have inaccurate ideas about school quality. Multiple surveys have found that parents incorrectly think that their child’s school is doing a great job. Despite scores on international tests that lag behind those of other rich nations, US parents tend to rate their own children’s schools very highly. “Virtually every national poll shows that although only a fifth of Americans rate the nation’s public schools very highly, some 70 percent of us think that the schools our own children attend are doing just fine,” explains Peter Schrag, writing in The Atlantic. He points out that some education experts even have a name for this false sentiment: “retail complacency.” The phenomenon is very consistent in the US.

The authors of the 2001 NCLB legislation did not witness the results that they expected, even as the law greatly enhanced parents’ opportunities to select better schools for their children: schools did not improve. A NY Times article titled “Failing Schools Strain to Meet US Standard” describes multiple reasons why up to 87% of consistently failing schools managed to avoid the harsh penalties that the law mandated, starting with a lack of funds to improve those schools and the limited reach of federal law when it comes to education.

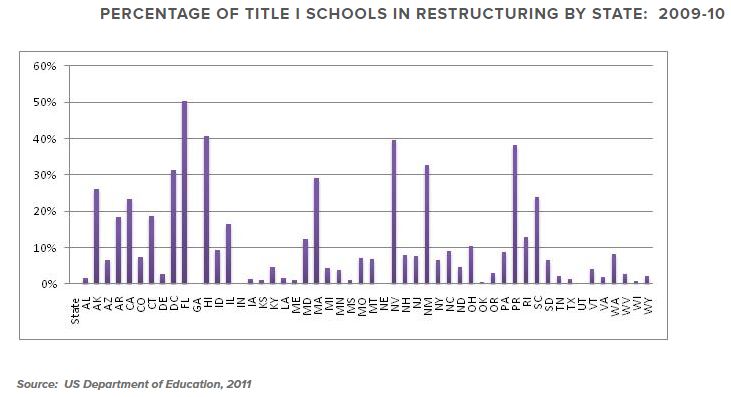

Another reason for inaction to address poorly performing schools was simply that states were overwhelmed by the numbers of schools that required expensive remediation. Here’s an example of how bad it got; this chart reflects Title I schools after 7 years of NCLB (which went into effect in 2002). Entering the “Restructuring” category levied the harshest penalties and indicated that students’ test scores had failed to demonstrate Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) for at least 6 years in a row:

In the 2003-4 school year, only 23 percent of public schools in Alabama and Florida made the AYP cut. NCLB included multiple tools to empower parents to yank their children out of failing schools, or to demand supplemental remedial services from those schools. But a huge majority of families did not take advantage of either option.

In their defense, parents rarely have enough information to select good schools for their children. Political scientist Lesley E. Lavery of Macalester College argues in a 2015 research paper that while NCLB was still in force, parents were unlikely to exercise their options under the law because they did not understand them—they were obscured in a fog of legalistic and technical jargon. Lavery hypothesizes that, “Rather than NCLB directly structuring school experience and arming parents with the knowledge necessary to take advantage of opportunities for improvement, perhaps the policy [was] designed and delivered in such a way that parents [were] simply under-informed about this policy and its potential consequences and opportunities” (Lavery Section 3).

She seems to be on to something. The US Department of Education conducted extensive surveys of parents with students at Title I schools four school years after NCLB went into force. They found that a large majority of the parents who reported that they had received notifications from their child’s school about their options to change their child’s school assignment or to enroll him or her in free supplementary programs, such as after-school tutoring, also reported that the communications they received “did not contain basic information such as how to apply to move their child to another school, whom to contact with questions, or availability of transportation“ (p xviii). The research report also noted that a paltry 17% of eligible students had been enrolled in these supplementary programs, while only 1% of students had exercised their option to select another school (xvi). They added that at high-poverty schools, the eligibility rate for supplemental educational programs was about 29% (xvi).

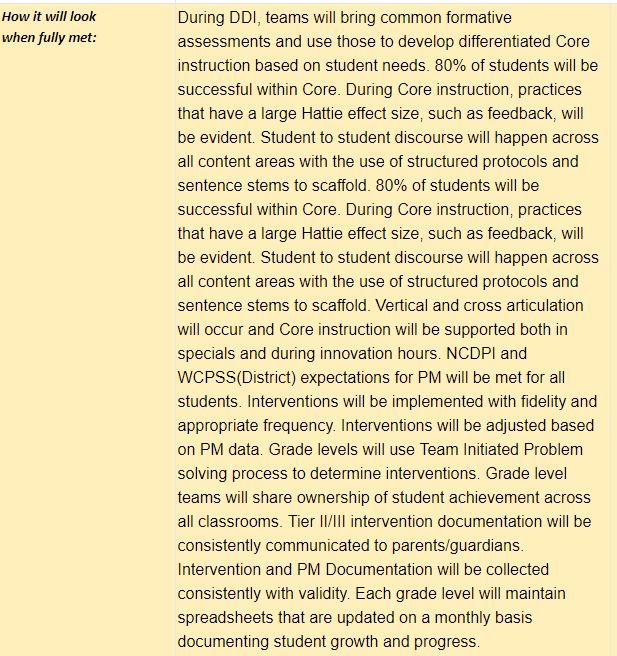

Here’s an example of a WCPSS school improvement plan, required by NCLB if a school fails to meet growth targets for two consecutive years:

Nowhere in the plan does it mention parental options associated with continued failure at the school. The jargon is dense, and the report is repetitive and confusingly worded. The law requires that some form of these reports be sent home with each child at each failing school. However, these reports do not spur parents to take action; the Dept. of Education noted that even as the numbers of eligible students rose each year (with each year’s test results from underperforming schools), the participation rate of 1% in the school-choice option under NCLB remained very stable.

Policy analyst Jason Bedrick argues that NCLB school choice was driven by “technocratic” standards. He underscores the inadequacy of test scores as the sole standard by which to judge school quality by describing the typical parent’s decision-making process: “Parents consider a school’s course offerings, teacher skills, school discipline, safety, student respect for teachers, the inculcation of moral values and religious traditions, class size, teacher-parent relations, college acceptance rates, and more” when exercising their school-choice options.

But Bedrick also admits that parents typically lack the required information to make good choices for their children. He believes that the opacity and paucity of the information that is available about each school has a historical basis:

The K-12 education sector has historically lacked high-quality sources of information about school performance, but to a large extent that is because the vast majority of students attend their assigned district school. With little to no other educational options, there has been little parental need for information to compare competing options. And without much in the way of competition, existing private schools don’t feel great pressure to be forthcoming about performance data. However, as states implement educational choice policies, the demand for information will increase and schools that refuse to share their data will be at a competitive disadvantage. We are already seeing parents turn to organizations like GreatSchools.org and Niche.com to find information about schools they are considering and we should expect to see more organizations emerge as demand increases. (EducationNext, Dec. 2016)

If you’ve ever tried to use The Niche or GreatSchools to make a decision about a school for your child, you recognize the limitations of these tools. They rely on input from (most often disgruntled) students and from parents who, as we’ve already discussed, can’t actually get reliable information about the quality of a school and don’t necessarily prioritize the learning environment above other, less important factors. (The Niche even provides ratings of the food served in each school district.)

If policymakers are going to continue to push for school choice, they need to provide better ways to measure and communicate the quality of individual schools. As it now stands, “school choice” presents a conundrum for parents, most of whom surely would prefer to see high-quality academics, sports, arts, and clubs at all public schools in their area. When you can send your child to a good school on the school bus each day, a very great source of worry and stress is virtually eliminated from your family’s life. The high-quality public schools that the majority of parents desire not only educate their and their neighbors’ children, but also shore up entire communities.

Is “school choice” just a cop-out, a way to avoid the expense and effort required to improve all public schools?